Money is power

An inconvenient truth when it comes to urban environments around the globe, where wealthy corporations are taking advantage of their fortunate position at the expense of the many less fortunate inhabitants. Whereas cities are the spaces where those without power get to make a history and a culture, says Saskia Sassen. ‘If the current large-scale buying continues, we will lose this type of making that has given our cities their cosmopolitanism’, she warned already two years ago in The Guardian.

Empty buildings

Sassen: ‘And it is not diminishing. One issue is the familiar fact that it is a way of cleansing one’s irregular wealth – to put it kindly. But it might also involve two other things. First, it is a form of buying urban land, which is often far more difficult to own than the building on top of the land; secondly, it can be used by investors to play the financial markets. Notably, making asset-backed securities that can be bought and sold easily – where the building or some part of it is the “asset.”.’

Sassen would even argue that if those buildings are sitting there half empty, they are still delivering profits to their owners via their financializing. And many of these buildings are empty. The ones that are not, are typically used for office spaces for large companies, luxury housing, pushing the less fortunate to live farther and farther away from the center.

Sassen: ‘We have to fight against this, put pressure on the political classes, on city mayors, communicate the negatives, and invoke the fact that the middle classes lose because the price of getting a home or workspace in these cities is extremely high so they wind up often with very long trips to work or very small flats in the center.’

Exchanging mattresses

‘I have been interested in understanding how marginal groups can also construct a type of space for themselves which works for them. By marginal I mean not only the poor but also socially marginal groups – in many parts of the world this would include gay and transgender people, those who contest an existing system, and so forth.’

These marginal groups all can, and often want to be participants in spaces that are really focused on some set of specific issues, she states. ‘For the poor, it might be about helping each other by exchanging mattresses for tables. Rich people who hunt might organize private meetings to exchange information about hunting deer with big horns.’

The street as a third place

Another topic in Sassen’s line of interest is to recognize ‘the street’ as a third place. That is not to say the street should become a place where marginal and non-marginal groups hang out together. Sassen employs a more sociological definition of the term ‘third place’: ‘It is an ambiguous term that captures an ambiguous condition. It can be applied to many diverse types of conditions, but it also signals something that is either emergent or unfamiliar, something that is neither ‘here nor there’.’

In the case of the urban condition, Sassen continues, it signals a type of space that is neither city nor suburb. It can take many different formats, say private corporate parks with many office towers, with guards, no housing. ‘But perhaps it can also capture the irregular settlements that keep adding to – say to rent out to others – family members, low-income workers, and such.’

On another scale, Sassen has used the term third space to capture the interconnection between the city and the make a connection between the environment and the city – a space where the city uses the biosphere’s capabilities (e.g. bacteria, algae) to handle diverse urban conditions, rather than say plastics and chemicals. A third space then becomes an in-between zone – in this case between the city and the biosphere. This is an abstract notion as opposed to a physical space or building. One might even consider digital places third places: any place that is not one where someone would normally spend time at, like at home or at work.

A people’s place

The latter definition might be the one most applicable to the street as a third place. We don’t necessarily hang out there – although some people actually do – but we all use it, to get from A to B. So, in the debate about the negative developments in our cities, we should acknowledge the street more as a place that is owned by everyone – hence, where everybody should be able to feel safe and comfortable – a simple, light, mode of sociability. Whereas Sassen as a sociologist is not active per se in street design, she does support the more positive

employment of the term third place: a place where people actually like to be, next to their first place – home – and their second place – work or school.

Sassen: ‘What I care about and like to emphasize about the street, is that it is a people’s place. And no, I’m not thinking of highways or major streets full of buses and trucks. I think of the street as a kind of indeterminate space where actors from many diverse worlds come together.

Where those who feel that they might not belong in a park such as the Jardin de Luxembourg, can feel that the street is also their street.’

We can only hope that our local governments are willing to learn from Saskia Sassen’s sharp observations and important learnings, so that maybe in the near future our cities can be actual cities again, instead of only a number of large-scale, concrete buildings serving the rich and wealthy.

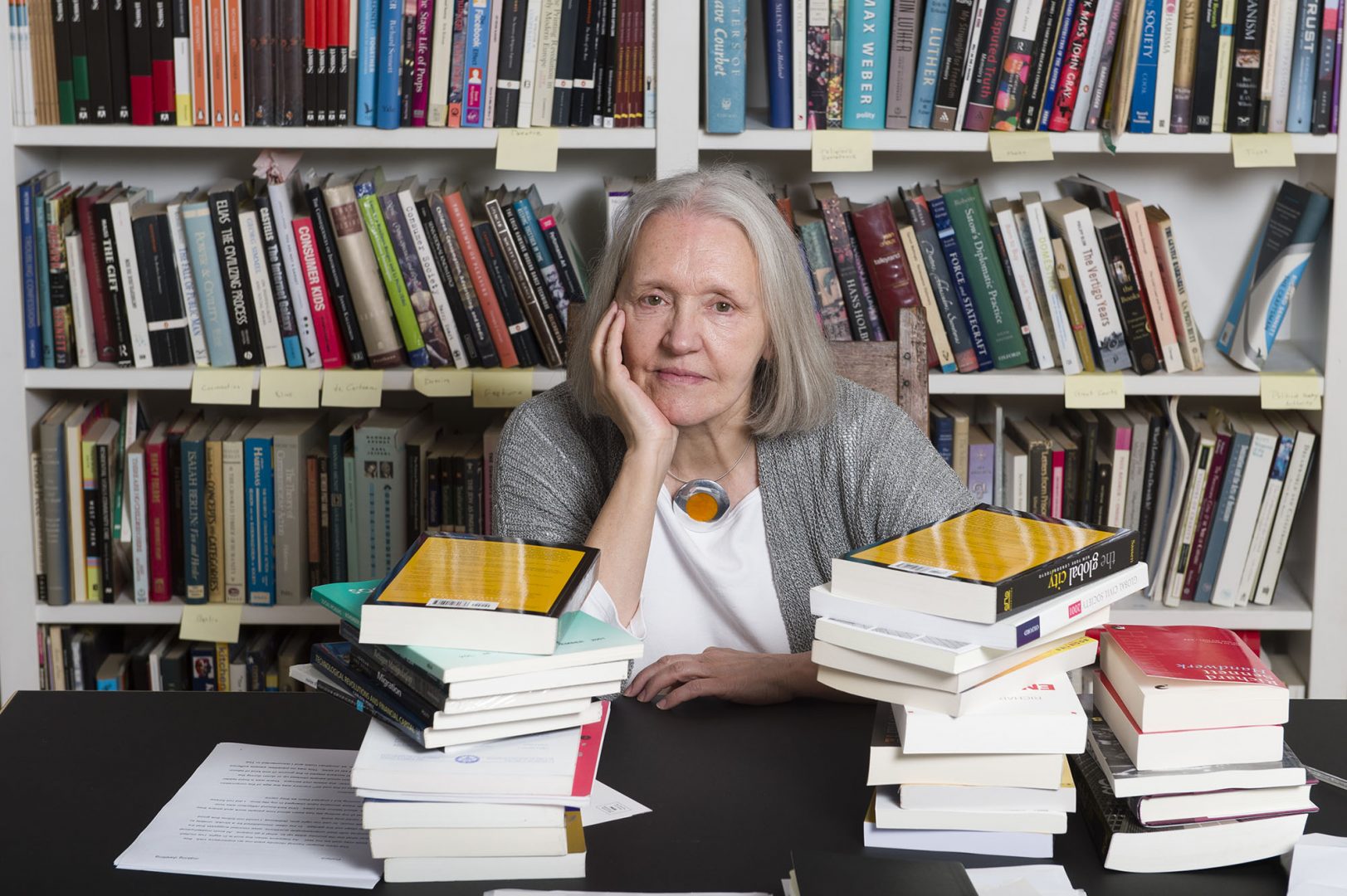

About Saskia Sassen

Saskia Sassen is the Robert S. Lynd Professor of Sociology at Columbia University and a Member of its Committee on Global Thought, which she chaired till 2015. She is a student of cities, immigration, and states in the world economy, with inequality, gendering, and digitization three key variables running through her work. Born in the Netherlands, she grew up in Argentina and Italy, studied in France, was raised in five languages, and began her professional life in the United States. She is the author of eight books and the editor or co-editor of three books. Together, her authored books are translated into over twenty languages. She has received many awards and honors, among them multiple doctor honoris causa, the 2013 Principe de Asturias Prize in the Social Sciences, election to the Royal Academy of the Sciences of the Netherlands, and made a Chevalier de l’Ordre des Arts et Lettres by the French government.

Read more on saskiasassen.com

Article by Claudia Ruigendijk.

Photography by Alex MacNaughton

Architecture Adapting To The Brand Ecosystem